Jonathan Morris, coffee historian and Professor of History at the University of Hertfordshire, shares an extract from his latest book - Coffee. A Global History. Here he tracks the development of coffee shop culture through the ages from Ottoman Coffee Houses to the lifestyle specialty chains of today. By Professor Jonathan Morris

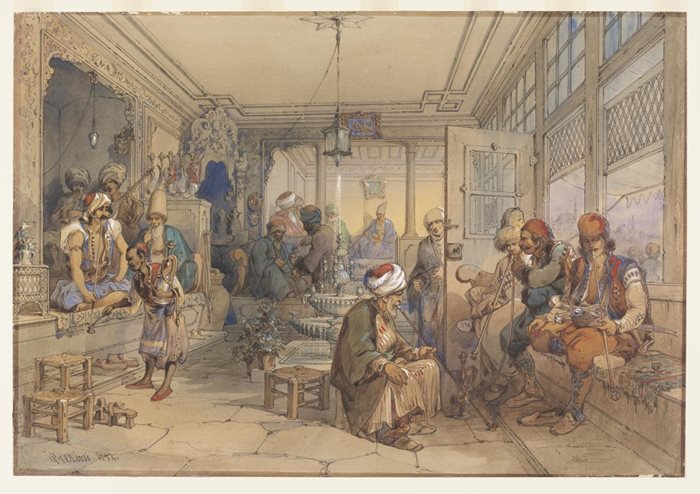

Amedeo Preziosi, A Turkish Coffee-House, Constantinople, 1854.

Amedeo Preziosi, A Turkish Coffee-House, Constantinople, 1854.

The growth of specialty coffee over the last 30 years has been based on a coffee shop format that has shifted the perception of coffee from a banal everyday product into a premium lifestyle one.

The concept of the coffee shop did not suddenly reveal itself to Howard Schultz, but has evolved over some 550 years of out-of-home coffee drinking. Many key elements were present in the very first coffee houses. Analysing the history of the coffee shop helps us understand variations in practices in different markets, dangers demonstrated by failed strategies, and possibilities for the future.

In

Coffee. A Global History, I argue that there have been five

eras of coffee history, during which the configuration of production and consumption led coffee to be characterised as: 1. Wine of Islam, 2. Colonial Good, 3. Industrial Product, 4. Global Commodity, 5. Specialty Beverage. During each era a new dominant format for out of home coffee drinking emerged, elements from which contributed to the international coffee shop format of today.

1. Ottoman Coffee House

Coffee houses first appeared in the Arab world during the 1500s after religious authorities ruled it was legitimate for Muslims to drink the non-intoxicating beverage. The ‘wine of Islam’ spread throughout the Ottoman Empire with the first coffee houses opening in Istanbul in 1554. By 1595 there were over 600.

Their success reflected the fact that they provided the first space where Muslim men could meet and socialise together beyond the mosque. Coffee houses treated all their customers as equals, seating them in the order that they arrived on long benches or divans running along the walls, rather than according to the privileges of rank. Men would met to talk, to gamble, to play backgammon and chess, and to buy each other cups of coffee as gestures of friendship. They listened to storytellers and musicians, or sat in scented gardens, during the cool of the evening, breaking their fast during Ramadan with an evening cup of coffee. Above all they smoked tobacco.

These democratic aspects of coffee houses were at times frowned upon by the authorities, who feared unregulated conversations could spark sedition. In 1633 Sultan Murad IV issued a decree that ‘anyone who opens a coffee house should be strung up over its front door’, yet their popularity amongst soldiers and public officials was such that bans proved impossible to enforce.

Kavehaz in Budapest, Hungary 2006. Interior of the restored coffee house originally opened in 1894.

2. European Café

Coffee entered Europe in the 1570s but was used for medical purposes up until 1652 when Pasqua Rosee, an Armenian émigré to London, opened the continent’s first coffee house. By 1739 there were 551 coffee houses in the city – one per 1,000 head of population. As coffee was seen as promoting mental performance, the merchant and professional classes used coffee houses to exchange information and transact business amongst themselves. Coffee houses became known as ‘penny universities’ as the price of a dish of coffee enabled patrons to read the house newspapers, view the ‘cabinets of curiosities’ and participate in the debates that were staged within them.

Tavern owners greatly resented these new forms of hospitality, but were unable to prevent them as they had no need of an alcohol licence to operate. When coffee houses did start adding alcohol to their offer, they soon became indistinguishable from pubs – by 1815 there were only 12 so-called coffee houses left in London.

Alcohol played a very different role in the evolution of the European café. In France, the distillers’ guild was granted the right to serve coffee to seated customers on their premises. This created the café format in which both coffee and alcohol might be ordered in the same premises, enabling cafés to trade from morning to evening and beyond. The Café Procope in Paris, established in 1686, set the trend, modelling itself on an aristocratic salon, with gilded mirrors, marble tables and painted ceilings, providing a club-like setting for eating, socialising and gaming amongst the elite. The Parisian café became so integrated into working class life that by the 19th century nearly a quarter of all couples asked their local proprietor to witness their marriage. In 1720, Paris counted 280, by 1790 there were 1,800.

3. The American Diner

Coffee was transformed into an industrial product in the USA where per capita consumption trebled between the 1850s and 1950s. The rapid expansion of production in Brazil kept the price low, enabling coffee to become an everyday item consumed in 98% of US households by 1939.

One factor in coffee’s success was the American proclivity to drink it throughout the day, both with and between meals: a common practice among soldiers during the Civil War. Subsequently coffee breaks became institutionalised at the workplace, while cafes and soda fountains flourished as prohibition turned coffee into the legal beverage of choice during the 1920s. Truck stops and roadside restaurants sprang up to brew up for an increasingly motorised society.

The American diner bought these trends together, offering ‘bottomless’ mugs of coffee refilled from the pour over jug stored on the hot plate. An American ‘cup of joe’ might present as thin and over-cooked to contemporary palates – but its cheapness, convenience and abundance, perfectly reflected coffee’s positioning as a mass market product in and outside of the home.

A classic American diner known for serving bottomless mugs of filter coffee

4. The Coffee Bar

After the Second World War, coffee became a global commodity with the rapid growth in robusta production, much of which found its way into soluble coffee products. Fast service snack bars appeared across Europe offering affordable bites and beverages, which customers queued up to order over the counter.

In Italy, the advent of the high pressure, espresso machine, able to rapidly brew coffee for each customer on demand, established a new form of coffee bar culture in which the beverages consumed at the bar differed from those available at home. The maximum price imposed for ‘a cup of coffee without service’ encouraged Italians to take their coffee standing up, while the low margins protected family run enterprises against the emergence of chains.

In 1950s Britain there was a short-lived coffee bar boom as outlets combined Gaggia machines with juke boxes to target young people who felt excluded from traditional pub culture. The combination of television, higher rents and pubs introducing sweeter tasting lagers killed off this format. The primary requirement of snack bar coffee was that it should be cheap.

Starbucks' ultra premium Reserve Roastery in Shanghai, China - opened December 2017

Starbucks' ultra premium Reserve Roastery in Shanghai, China - opened December 2017

5. The Specialty Coffee Shop

In the 1980s, US specialty pioneers adopted espresso machines to present Americans with hand-crafted gourmet beverages whose theatrical preparation and exotic appearance were used to justify prices far removed from those prevalent in Italy. Changing the coffee was the key to changing the fortunes of the coffee shop. Whereas the US diner offered subsidised coffee as part of its service proposition, the specialty coffee shop subsidised its service proposition through the price of the coffee. Coffee was the rental charge for enjoying the premises and what they had to offer, much as with the Ottoman Coffee House.

The speed and convenience of the coffee bar were incorporated into the coffee shop format with the communal queue conveying the egalitarian nature of customer service. The rise of the mobile device enabled coffee shops to revert to the role of alternative workspaces as with the English coffee house, yet much of their appeal stems from offering the sense of a ‘third space’ in which the neighbourhood can meet, much like the Parisian café.

The most significant achievement of the specialty coffee shop may yet lie in the future. Already chains such as India’s Café Coffee Day have succeeded in making coffee an aspirational beverage among the country’s young middle class. If this were reproduced across the global south, it could have major implications for the sustainability of the industry as producer countries become consumer ones, raising demand in line with supply, and ushering in a sixth era of coffee.

Jonathan Morris is Professor of History at the University of Hertfordshire and author of Coffee. A Global History, published by Reaktion Books at £10.99. Readers can get 20% off the book by visiting their

website and entering the code COFFEEPOD. Bulk order discounts of up to 50% are available through the publishers. Follow Jonathan on Twitter @coffeehistoryjm or visit his website

www.thecoffeehistorian.com