How innovative technologies like blockchain are being deployed to improve coffee supply chain scrutiny and secure better incomes for farming communities. Christopher Jordan, Coffee Manufactory COO, explains the development of Direct Trade 2.0. By Tobias Pearce

Whether its Fairtrade, Rainforest Alliance, Café Direct or an increasing number of custom-built coffee accreditations, there are a plethora of ethical coffee labels available. But with each adhering to different standards it can be difficult to discern the cacophony of sustainability marketing. So, just what do these standards represent and how far can we trust they truly benefit those who produce our daily cup?

Christopher Jordan is COO of US-based Tartine Manufactory and its wholesale roasting division,

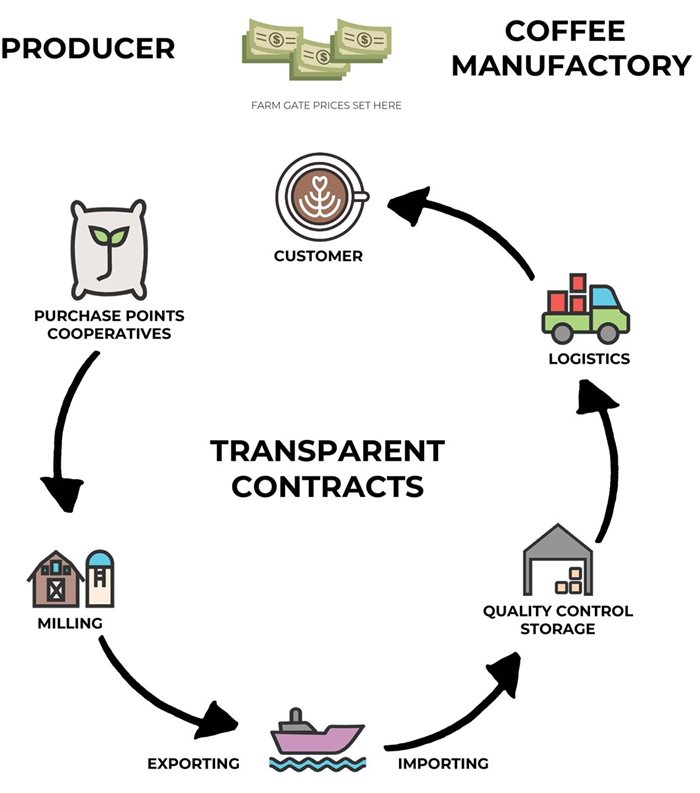

Coffee Manufactory. Over the past year he’s been on a mission to develop a coffee supply chain methodology that can verify best practices by providing both buyers and farmers with data transparency from multiple points in the procurement process.

As Director of Quality at Starbucks Coffee Trading, Jordan was involved with developing the US coffee giant’s flagship Café Practices accreditation. Now, having also worked with

TechnoServe’s Coffee Initiative – a Bill and Melinda Gates funded initiative in East Africa and successfully leading several coffee companies over the years – Jordan is culminating his deep knowledge of coffee supply chains to forge a bold new direct trade model. Today he's working with Californian cold brew gurus Califia Farms and UK-based specialty green coffee trading business Falcon Coffees to realise his vision.

“Millions of dollars is spent on certification because companies need to feel protected. But slapping a label on a product is a lot easier than traveling to origin every year"

Some accreditations are more reliable signifiers of supply chain performance than others. It’s therefore essential that each transaction from bean to cup can be verified to measure and guarantee farmer profitability. “When we first got in touch with Califia we initially said we wanted a certification, but they emphasised that the future was Direct Trade because certifications have their own stigma and shortfalls,” says Jordan.

“Millions of dollars is spent on certification because companies need to feel protected. But slapping a label on a product is a lot easier than travelling to origin every year, collecting transparency information from producers and understanding how much farmers receive versus FOB price.”

And technology is enabling greater coffee trading in remote producing regions that wasn’t possible when Jordan first travelled to Africa. “When I first went to Ethiopia in 2002 there was no cell coverage and certainly no ATMs. But things began to change with increasing urbanisation, markets opened up and cell phones became more prevalent, even in rural areas,” Jordan says.

Indeed, mobile technology is crucial to what he calls Direct Trade 2.0. In partnership

Califia Farms and

Falcon Coffees, Coffee Manufactory is trialling a new direct trade initiative in Colombia and Uganda. The aim is simple: to improve income for smallholder farmers and safeguard coffee production for future generations. Realising this vision is, however, a hugely complicated task involving multiple stakeholders and differing local circumstances.

Combined, Coffee Manufactory and Califia Farms roast almost 20 tonnes of coffee per week, making them sufficiently scaled for their model to be commercially effective. “Our ability to go outside the spot market or the local market and buy container loads of coffee allows us to do this work. For smaller roasters buying 25 bags it would be very difficult to travel to origin, let alone invest in a new sustainability platform,” says Jordan.

"We believe if you get the right KPIs and the right technology, like blockchain, ultimately producers start owning more of the process"

But as Jordan points out, coffee supply chains differ greatly across global markets, whether they’re cherry-based supply chains in El Salvador or parchment-based as in Rwanda and Uganda. To better generate value for producers, each supply chain has critical points where data must be captured, and this is where blockchain technology is coming to the fore. It may be more eminent among crypto-currency circles, but blockchain could enable Coffee Manufactory to capture complex supply chain data as never before.

In Uganda, Coffee Manufactory has been working with Falcon Coffees, which has created a business model around traceable and verifiable coffee supply chain metrics. Falcon, headed by Jordan’s long-time friend, Konrad Brits, has developed its own blockchain methodology called

Blueprint. It’s essentially a dashboard that allows supply chain partners to capture offline transactional data throughout the supply chain via smartphone, even down to the farm household level.

To measure the efficacy of the system, Jordan and his team, together with Scientific Certification Systems (SCS) has developed 12 KPIs covering aspects such as health, education and farmer income. These KPIs will be measured by feeding captured data into Blueprint to verify each transactional stage. The idea is that Blueprint could eventually allow all stakeholders in the coffee production process to verify ethical credentials and monitor value throughout the supply chain.

“For many years there’s been a huge number of players in supply chains. We believe if you get the right KPIs and the right technology, like blockchain, ultimately producers start owning more of the process – our KPIs are not intended to be certifications,” explains Jordan. Instead, the KPIs are designed to provide producers with an opportunity to obtain data ownership while promoting and enhancing their sustainability efforts.

“This is one of the first times we’ve actually been able to capture data from farm to customer at each of those critical supply chain points. They work around household income, farm mapping, supply chain mapping, transparency, and they’re able to capture most of it via mobile phone from start to export, all the way to our side and to the customer,” says Jordan.

The pilot projects in Colombia and Uganda are still in their early stages, but the application of this radical technology is allowing scrutiny of supply chains that until now often been obscured by complexity. But how could Coffee Manufactory’s direct trade model manifest in the coffee shop?

“Most consumers have very little time for a lot of detail and coffee supply chains can be very confusing. Put simply, we have to communicate that the farmers we work with receive at least 75% of FOB price. As we evolve, we’ll have to articulate to consumers that this is a sustainable price for farmers so they’re able to have a margin and put money in the bank.”

There's been widespread coffee industry alarm since commodity coffee prices fell below $1 in August 2018, . But even high-profile action, like

Starbucks’ $20m fund for struggling Central American farmers, won’t tackle systemic economic problems facing the world’s poorest producers. Jordan has witnessed the detrimental conditions caused by sustained low coffee prices first hand and emphasises that market volatility is only bad news for the coffee industry in the long-term. “There needs to be focus by the industry or you’re going to see a backlash. Farmers will transition out of coffee and the market will go to $2. This ‘yo-yo’ effect will only continue to hurt the industry and hurt quality,” he warns.

Advances in technology could equip businesses with tools to better comprehend complex supply and previously opaque supply chains and make procurement decisions that truly benefit coffee farmers. Whether it’s scanning a QR code or more specific origin labelling, transparency and traceability offers the potential for far greater ethical scrutiny – and an opportunity to consumers to start voting with their feet when it comes to the fairest coffee in town.